|

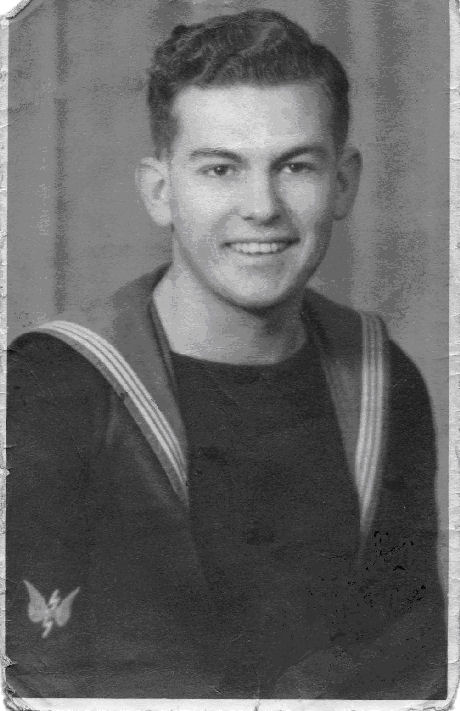

I suppose I should start my story in a war ravaged Eastbourne in Sussex on the South Coast. I ran away to sea at the age of 15 but was thrown back as being too young apart from being a bit on the small side, thanks to a 1930’s depression.

A strange thing: down in Eastbourne it seemed to be impossible to get anyone to take you seriously about joining the navy at such a young age so I joined the Sea Cadets and was advised by a wise old three badge instructor that the easiest path was to become a member of the communications branch. Thus, having done all the things that Sea Cadets did in those days: boxing the compass, tying knots, rifle drill, marching, going to Church parades etc., I commenced the learning of morse code, reaching the necessary eight words per minute..

I might digress here for a moment: on completion of one Sunday Church Parade, while passing the railway station heading towards the usual bus stop in Upperton Road, 14 German fighter bombers roared over the area, machine gunning and dropping 500lb high explosive bombs as they went. One H.E. hit the building behind me and I was blown off my feet. On recovering I assisted another victim, who looked terrible, to his feet and advised he go to a first aid station near by. A bus conductor told me I looked terrible too and suggested I might go to the Aid Station. Arriving at the Aid Station I joined in with several others. While waiting, another casualty, told me he was Jimmy Wild, a well known boxer. Jimmy had a pale green palour. It subsequently transpired that paint from the rather ancient building that had been subjected to the bomb blast had virtually vaporized into a pale green powder and had settled on us, thus making some of us look worse than we were.

At the Aid station, at my turn, after my naval uniform was removed, I was injected with large quantities of anti tetanus serum, taken to hospital and placed in a bed next to a Canadian soldier. Some object had penetrated my back causing a deep wound and making a hole in the uniform of which I was so proud, soaking it and three other levels of clothing with blood. Three weeks later I was able to return to my learning the morse code.

Then came the day when a railway warrant arrived and I was off to Brighton where forms were filled in, a medical examination carried out and I was sent home to anxiously wait. My call up papers arrived around the time of my 17th birthday I was to join the navy through the ‘Bounty’ scheme. A very excited cadet, along with a cadet friend who had been learning the art of visual signaling caught the train and their way to Grenville Hall in Stoke Poges Lane, Slough, Bucks. The instructors were sailors who, for some reason, were no longer fit for sea duty.

After completing a month at Grenville Hall, the class moved on to HMS Royal Arthur, a Butlin’s holiday camp in Skegness where kitting out with new uniforms, pay books, vaccinations, inoculations were all completed as a joining routine. Morse training was continued as well as marching plus anything the navy thought we should be doing at the time, that included looking for butterfly bombs that may have been dropped overnight and a duty called “Jim Crow” where one patrolled a roof looking/listening for enemy aircraft that flew over during the night.

The vaccination injection had affected me rather badly and I still had a pretty high fever when joining the train at Skegness station. I had spent most of the previous week laying on my bunk at every opportunity there wasn’t a demand for my presence. An air raid delayed the train by an hour or two. As I sat (slumped) in my seat on the railway carriage a rather amazing sensation took place: I could feel the fever draining away, just leaving me feeling weak but without fever. It took some 22 hours for the train to travel from Skegness to Ayr in Scotland after being diverted a couple of times.

On reaching Ayr, I was detailed off to put all the kitbags and hammocks on to a truck. Even in my considerably weakened state, asking to be relieved of this task or arguing wasn’t an option. HMS Scotia, another Butlin’s holiday camp was to be home for the next five months. A concentrated course for wireless telegraphists was persued. No diversions like squad drill etc having done much of that in the Sea Cadets. We became very professional in those five months: reading and transmitting morse, learning an intricate procedural system, theory and practice on electronic equipment, coding, some visual signaling, with each subject having evening backward classes should one drop behind, plus threats of being sent off as stokers. Although my standard was good, I attended the ‘backward classes’ sometimes ticking off the name of someone who should be there!!

The five months ended with a spell of leave and drafting to HMS Mercury at Leydene, Petersfield which, at the time was an (rather primitive) establishment for communicators. After a week or more of waiting for a ship I became restless so when there was a request for some of the fledgling telegraphists to train as Tels(S), a course on learning the U-boat organization, how to detect U-boats on a new direction finding set, I accepted the offer.

A three weeks course for Tel(S) was held in Eastbourne followed by practical training at Leydene. There was again some delay which had me being sent to collect deserters. At least the alteration to my status as Tel(S) ensured I would be sent to an escort vessel. The wait was relatively short when the crew for the new vessel HMS Volage was directed to Royal Naval Barracks Portsmouth from various establishments around Southern England.

After a successful “Warship Week” Volage had been adopted by the citizens of Pocklington but this was unknown to me when, with bag, hammock and suitcase I climbed aboard the Naval bus for Portsmouth naval barracks, with excitement and the enthusiasm of a seventeen year old.

Following the inevitable Joining routine at RNB a few days were spent there until all necessary crew members arrived. Portsmouth was subjected to a number of night air raids that caused all of the barrack’s residence to be aroused and ordered into the shelters under the parade ground.

In a very few days a drafting routine to leave the barracks was followed by the bulk of the new crew, marching to the waterfront and embarking onto a transport vessel, to be carried across the Solent to Cowes on the Isle of Wight.

Debarking onto the wharf at Cowes our new home was tied alongside the wharf nearby where we assembled to be received by the captain: Commander Durlacher. After a short welcoming speech the Chief Bos’n’s Mate directed us to our respective messdecks.

The communications staff were directed to their messdeck right for’ard along the ‘iron deck’ on which we first stood when boarding the vessel. Then down one ladder to the lower for’ard messdeck. In this brand new messdeck: on the starboard side, there was a table and chairs all bolted to the deck. Around the bulkheads there was padded seating. A hammock stowage rack, a locker per person. Across the ship there were railings just below the deckhead to which the hammock could be attached, one to a person and just enough room for all of the hammocks to be slung at one time if they almost touching. Climbing into the hammock was soon mastered, pushing your hammock aside so as you climbed in so your neighbour would not be disturbed. Finally a couple of portholes either side close to the waterline and an escape hatch

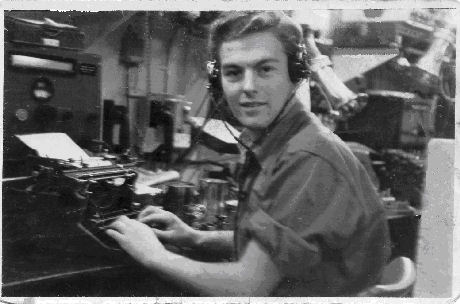

Next on the agenda, was to make our acquaintance with the rest of the w/t staff who had been with the ship since its launch in December 1943. This done and personal effects stowed away all newcomers did a ‘Joining routine’ that included obtaining a ’Station Card’ that identifying our watch(port or starboard), mainly for leave and work detail, getting a pay number etc., then along to the W/T (Wireless Telegraphy) Office to meet the Pettty Officer Telegraphist. Here each was notified the ‘office watches’ to keep. In the main there were to be in three watches at sea, one watch on and two off. It was quickly learned which watch would clean the messdeck, which one would clean the office, the other watch of course would be on watch in the office. In harbour the comm. staff would go into a four watch routine and it was possible that the fourth watch would be able to go ashore during the day.  Off duty communications staff.

4th from the left wearing glasses is Jeremiah McMahon RN Comms Tech

Off duty communications staff.

4th from the left wearing glasses is Jeremiah McMahon RN Comms Tech

(from information sent by his grandson Jon McMahon 29/3/20) A new life and the beginning of a new routine on a new ship had started. The watch whose turn it was to clean the messdeck, would prepare morning tea and the mid day meal, taking the prepared meal to the galley to be cooked. Small ships such as destroyers were on ‘Canteen messing’ which meant a certain amount of food was allocated to each mess with member of the mess being responsible for adequate stores being ordered. Should the mess use more than the allocation, then the cost of the difference would have to be paid for.

On that first day there was no ammunition on board so when the air raid sirens were sounded during the evening the guns remained silent. So did the majority of the crew who remained in their hammocks. Cowes was a target that night but the men in their hammocks slept sublimely on. At first light, an aerial mine could be seen swinging from a power pole around a couple of hundred yards away. Commander Durlacher, the ship’s captain was not amused at the ship’s company’s non action at the sounding of the air alert. He stressed that staying aboard in an air raid under such circumstances was not acceptable and that crew members were to find shelter ashore.

The situation did not again occur as Volage left the Cowes wharf the following day to anchor in the Solent. From this anchorage the ship carried out speed and manoeuvring trials. The off duty crew did get shore leave at the end of the day and went into Cowes. While ashore the weather deteriorated considerably and returning to the ship proved a very difficult experience, the ‘Liberty’ boat being a landing barge deck remained level with Volage’s upper deck for split seconds at a time.

After just a few days Volage departed the Solent for Scapa Flow traveling along the southern coast at night with my home town in complete darkness and unseen.  HMS Volage at Scapa Flow.

HMS Volage at Scapa Flow. The journey to Scapa Flow was uneventful. All attention was being paid to the amassing of ships in the English Channel region, and so on arrival at our destination, most of the Home Fleet was away. Volage tied up to a buoy and carried out normal harbour routine. The following day saw the commencement of final working up trials, with considerable attention paid to gunnery and practicing torpedo attacks. As far as I was concerned the FH4 radio direction finding equipment had to be calibrated and a correction chart made for use in operation.

The reason for calibration was because of the ship’s magnetic field causing signals to vary in apparent direction when received from different angles on the ship. Calibration was done by a tug circling the ship sending radio signals. The bearing of the ship measured visually was compared with the signal received by the FH4. Measured by both the angle of the trace on the cathode ray tube compared with the ship’s head and the gyro compass ring around the c.r.t., a slave to the ship’s gyro compass system.

The calibration took most of one day then a couple of days for a correction chart to be made up showing the radio errors due to the ship’s magnetic field. The H/F/ D/F system was now ready for operational use.

H/F/D/F Office FH4 Receiver

The working up trials completed in July, Volage was ready to take its place in the 26th Destroyer Flotilla as a half leader ready for active duty in the fleet.

Daily orders listed leaving harbour for gunnery exercises, torpedo firing exercises, exercising with the flotilla and on one occasion, it was the V destroyers’ lot to exercise with HMS Royal Sovereign, or as it was later called the Arkangelsk. Six of the ancient destroyers that had been passed to the Royal Navy from the Americans under the lend lease agreement, were passed on to the Russians. These destroyers, according to our daily orders, were also to exercise with the V’s and the Arkangelsk. There was a Force 10 gale with sleet at the time. Russian destroyers never left the anchorage. Rumour had it at the time that the Russian sailors had gone to their Union leader and suggested that it was too dangerous to take these ancient destroyers out in such weather. The V destroyers exercised throughout the daylight hours with the Arkangelsk. My post on the bridge on was manning the VHF transmitter/receiver. A heavy sea was running, snow and sleet caused one to hide as much as possible in the lee of the bridge where the SCR522 transceiver was situated. Hooded duffel coats, gloves of a similar material left the face only to the elements and but caused difficulty in operating the transmitter button through the thick gloves.

Early July saw the 26th Flotilla now including Volage leaving the anchorage at Scapa Flow in violent weather exercising with the fleet in preparations for air attacks on shipping and shore targets between Lepsoy and Haramsa Is., on the Norwegian coast. The extremely high seas, gale force winds and much of the time overcast skies with rain and sleet all a part of the discomfort that lasted for well over a week, tested newcomers to the full. Johnny Coates came off the ‘forenoon watch’ thus having a late lunch. Everyone else having had lunch and cleaned up, feeling the affects of the weather conditions were in their hammocks. Johnny a UA, that is, he was under age for being eligible for a rum ration, accepted the offer of a tot of rum from a fellow watchkeeper. The weather, the rum and possibly dinner all had effedt. Johnny was sick. Dutifully he cleaned it up, at the same time, the deck was subjected to water so of course that had to be cleaned up as well into the gash bucket. A particularly violent wave knocked a now almost full gash bucket over. Start again and no one game enough to leave his hammock to assist!!

On the 15th July Volage crossed the Arctic Circle at position 67° 30’N 4° 50’E for the first time to cross it numerous times during the year.

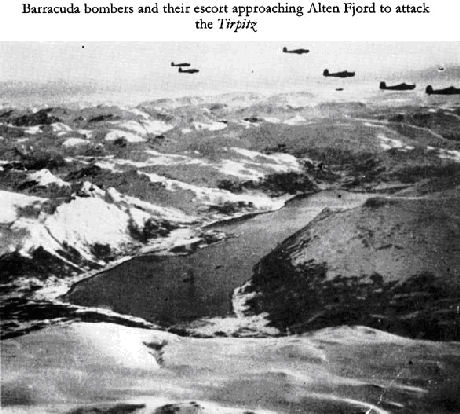

For the second operation the flotilla was part of the escort for a group of carriers HMS Indefatigable, Trumpeter, Nabob from the Home Fleet which covered the convoy JW-59. The carriers launched attacks (Operation Goodwood) on the German battleship Tirpitz at anchor in the Altenfjord.

During a break in operations escort vessels were refuelled from the carriers and it was at this time that the submarine U-354 encountered the fleet on its search for the convoy northwest of the North Cape in the Barents Sea. At about 13.00 hours on August 22, 1944 U-354 badly damaged HMS Nabob with a FAT torpedo spread and tried to sink her at 01.22 hours with a Gnat, which struck HMS Bickerton. HMS Bickerton was subsequently sunk by a torpedo from HMS Vigilant. Volage was in close proximity at the time of the attack and with the detonation of the torpedo on Nabob, it sounded like a huge hammer had hit the side of the ship.

Although severely damaged, Nabob was able to limp back to Scapa Flow but the damage was found to be sufficiently severe as to make it unviable to repair.

Raids were launched against the Tirpitz but invariably that vessel was hidden by smoke screens and from memory, shore targets such as radar sites and port installations were attacked

Convoy JW59 of 34 merchant ships in which the battleship Archangelsk formed part of the escort arrived in Russian ports with just the loss of HMS Kite. In turn, aircraft from the carrier Vindex sank the U-boat responsible

Convoy RA59A traveled through the area a little after the arrival of JW59 in Russian waters, on its way back to Scotland. I did receive a sighting report from a distant U-boat that had made contact with the convoy, the only sighting report on that frequency, however, U-boats did use more than one frequency. At approximately the same time that ships associated with Operation Goodwood(attack on Tirpitz) were departing the area and returning to Scapa Flow.

Life in Scapa Flow

Ships may remain in harbour occasionally for a week or so. In 1944 there were those destroyers whose names commenced with V and W then there were others that begin with O, U, T, the Tribals also stationed at Scapa Flow, a couple of Canadians: Algonquin and Sioux(ex V). Later there were the Z class. Apart from the Tribals, they all looked very much the same. All would take part in various operations off the Norwegian coast so there would be no respite from attacks on shipping and coastal installations. Minelaying by aircraft would also take place although Volage itself would not be involved in actual minelaying.

While in harbour there would be little relaxation. The wireless branch, now working in four watches, one on, three off, forever read the W/T broadcast from Whitehall. All messages thus sent were in four figure code using what was known as the “double subtraction stencil frame”. so that there was always an operator and a coder on watch. As the ship’s complement included only two coders, a w/t operator (all were fully trained in coding) would take the place of a third or fourth coder. The two senior ratings (leading hand and petty officer) would spend the daytime hours in the office on various tasks. During the evening watches when daytime traffic had died down, there was always exercising between ships, mostly sending dummy messages. Ship conducting these exercises would probably ask another ship to repeat messages back, even though dummy, serious charges would be brought if there was any breach in routine. Prior to any operation, a large amount of signaling was required to be carried out so in non operational times dummy messages were sent to mask the heavy operational traffic necessary before an operation.

Forenoon in the office, would see the designated watch personnel clean the office and take the confidential waste to the boiler room for burning. Warning: it was essential that on entering the boiler room, that one door of an air lock be closed before opening the second otherwise a strong draft of air would leave the boiler room drawing flames out of the fire door so depending on the location of boiler room personnel, could be a damaging situation My particular hate on taking the paper to boiler room to be fed into the fire, was all the cigarette residue included in with the paper and me being a non smoker, getting partly covered in cigarette ash was unpleasant.

The afternoon was free time for ‘watch keepers’ which included communications staff.. It was then that laundering of clothes could be done. Laundering: there was no laundry on board small ships so washing of clothes was done in a bucket using an immersion heater, soap suds were created by putting a bar of regulation soap in a used baked bean tin that had holes punched in it and swished around in the hot water. The rest was done by hand that included the medical officer’s recommendation of three rinsings.

It might be pointed out here that drying of clothes on the upper deck was strictly forbidden, wet clothes on the messdeck was also not permitted due to the messdecks already damp much of the time and a breeding ground for T.B. thus cloth drying was somewhat of an art: wet clothes being taken through an airlock, into the boiler room, there they would be strung out along a cat walk railing around the top of the boiler room. Then there was the occasional person onboard ship that would help himself to someone else’s clean underwear albeit each piece of clothing was marked with the owner’s name

Also the scrubbing of hammocks and writing letters home were carried out. If you had brought some books aboard with you or you could swap one, then it was a good time to read. From time to time daily orders would include a ‘make & mend’ for the ship’s company in the afternoon, mainly affecting the Seaman Branch. This really meant afternoon freetime, but in bygone days it was for the purpose of repairing or making clothes. It was also a good time to catch up with washing of clothes, scrubbing one’s hammock etc..

For the ‘watchkeepers’ in harbour there would be an off duty watch with no duties. This presented a problem during the forenoon as no one was allowed to be seen with nothing to do (termed: skulking). However, it became a culture to blend in with the ship at such times and I can’t think of any real problems.

After the usual ‘pipe’ “Libertymen fall in on the iron deck abaft the gangway”. at 1615hrs, a ferry would go round the fleet collecting up liberty men from all vessels, discharging them at the landing wharf just down from the naval canteen. At the canteen beer would be available. I don’t remember there being other alcohol available.

It was a case of buying tickets for the amount of beer you could afford, or thought you would consume. There was always a shortage of beer glasses, so one obtained a glass and held on to it all evening. The cinema, primitive as it might have been, showed the latest in British and Hollywood films. On returning to the ship one had some feelings of well being, after all it had been a break in a monotonous routine although a few beers for most would give the greater glow. Some of the crew went each time the opportunity came, others on the odd occasion which coincided with a fresh film being shown..

During the evening there would be the odd diversions for off duty crew members, one important item was always the making of ‘pussers kye’ this entailed the scraping of cocoa from a hard solid block then of course getting boiling water from the galley and finishing off with tinned milk. The finished product was a thick drink with quite a lot of unrefined cocoa oil floating on the top. Playing cards was regularly persued with the mildest of gambling. Listening to the BBC which was ‘piped’ throughout the mess decks was always appreciated: news from what was going on back home, other theatres of war and entertainment programmes were always a nice diversion. ‘ITMA’, ‘In town tonight’ ‘Flanagan and Allen’ ‘Bebe Daniels, many more of course Paddy, one of the coders, who appeared ancient by us of the 17 - 19 age group, no matter where we were nor weather conditions, seasick or not, would kneel down just prior to climbing in his hammock and say prayers.

There was the very infrequent opportunity daytime trips ashore in the Orkney Islands. Should you have been a year on and off at the anchorage, it is almost certain there would have been a visit to Kirkwall, the capital of the Orkneys. An ancient town with cobbled stoned streets, quaint little shops and people that kept largely aloof from sailors. At hockey the ship would challenge one of the flotilla to a game. Soccer, another change of routine for a few. Off watch communications staff were given the occasional opportunity of going ashore near the canteen for a walk around the countryside. There was a building where gunners of the anti aircraft kind would go to practice their profession. Said to be very realistic complete with all the noises of an air attack.

Beginning of September, Volage departed Scapa Flow and proceeded up the Clyde to Gourock where some repairs were completed in a minor refit although the main reason was for the ship to have its boilers cleaned. This allowed a short spell of leave for each watch. Then it was back to the business of war.

Mid September 1944 Volage with the flotilla leaves the anchorage for destination unknown (again) late in the day. The following day the major portion of the escort vessels are in Lock Ewe, northwest Scotland. A large number of merchant vessels had already passed out through the loch entrance, past the unlit Rubha’Re lighthouse at the entrance to the loch, to form up into a convoy heading northwards with seven warships in close support, for the Northern Cape of Norway, Barents Sea, then, either the Kola Inlet and Murmansk, or the White Sea and Archangel. And for most of the way a waiting enemy.

Two days later, the remainder of the escort departed Loch Ewe to join up with the convoy.. Convoy JW60 had the luxury of two aircraft carriers: Campania and Striker. A battleship: Rodney, a cruiser and twelve more destroyers to join up with the early escort. The convoy was under surveillance from just a day or two on its journey. B-Dienst, the German code breaking and naval intelligence team already knew all the details of the convoy, maybe not its day to day manuoevres, but code number, number of vessels etc., and roughly when to expect it off the northwest cape of Norway.

The convoy and escort proceeded on its way at the speed of the slowest vessel in company, around ten to twelve knots. The crews of the warships carry out their dawn and dusk action stations but no alarm had been sounded. The sea is quite moderate and so life is not too unpleasant.

With the convoy off the NW Cape, I am on watch on the high frequency detection finding receiver. Signals in four letter code, are coming in regularly from DAN, the German broadcast station. With thanks to Bletchley Park, advice has been received to change frequencies in line with the U-boats changing theirs. The sea is calm, the middle of September light is good at 6a.m. when a signal is received from a nearby U-boat. It had sighted the convoy and makes a ‘sighting report’ to DAN. A demonstration U-boat signal in training was: BB CON VOYS SIGH TED. The two B’s that identified the signal as coming from a U-boat were termed B bar as they had an accentuation bar over the top of the B. During the fifteen seconds or so that the signal took to complete, an intermittent elliptical trace would show on the Cathode Ray Tube, a bearing taken, the sense aerial switched to identify which end of the trace is required, correction made from the calibration chart. The signal came from almost dead ahead, well within the radio groundwave so I guessed it was around 20 nautical miles away. A message is quickly coded up in the ZR4 code and would look something like ZR4 CDWK. Using the voice pipe, the bridge is notified and details passed. Some fifteen minutes later, I received advice that an aircraft had been dispatched to investigate my report. The U-boat had been located on my exact bearing at a distance of 21 nautical miles. Of all the many U-boats I had detected, this was probably the most satisfying. The U-boat was attacked but without any positive result.

There were other U-boat sighting reports but the convoy traveled safely through the Barents Sea. On reaching the Kola Inlet some vessels docked at Murmansk. Some of the escorts, including Volage proceeded to the Russian naval base at Polyarnoe. Other merchantmen traveled down the White Sea to Archangel. JW60 a relatively speedy convoy due to more moderate seas than usual had arrived safely at its destination in seven days.

The crews of the escorts were allowed ashore and on leaving the ships were warned not to stray from the defined paths into the base. Huge nurses carrying similarly large rifles on patrol duties ensured that no one felt inclined to test out the instructions. There was some mingling with the local troops: it was discovered that one young sixteen year old soldier was convalescing at the local hospital after being bayoneted seven times. There was a gibbet at the base where it was rumoured that soldier deserters had been hanged as well as a sailor who had for some reason missed his ship when it sailed. Sports challenges were met among the escort ships companies which were conducted on the nearby sports oval. With the rarified air and lack of exercise facilities on a destroyer, running relatively long distance races had its effect on runners – in the quarter mile event a number of participants collapsed by race’s end. On the night before the convoy was due to sail, crews were invited by the Red Army Entertainment group to a concert in the local army hall. It was a very professional evening with some outstanding acts, especially from Cossack dancers. Before leaving the ship advice was given that to whistle in appreciation would be interpreted as insulting. Nothing was said about booing so sailors being what they are, in among the very energetic applause was plenty of booing, however, there was no whistling.

RA60 joined up at the entrance to the Kola Inlet and proceeded into the Barents Sea. Laying in wait was U310 and on the first night out sank the merchant ships SAMSUVA and EDWARD H. CROCKETT the fate of the crews went unknown. Volage and Veralum were detailed to remain behind the convoy and drop depth charges on a regular basis, an exercise known to deter the most rapid of U-boat movement, until the convoy was well clear of the area where it was known that several U-boats were on station. The two destroyers rejoined the convoy after twenty four hours to be challenged on their approach by the battleship Rodney.

Another forty eight hours passed. At 2345hrs, and enormous explosion shook the ship. The entire crew in the forward section, rapidly climbed down from their hammocks, headed through the hatches and doors, leaving the last one to secure them. Blowing up their lifebelts, a rubber ring type with a small red light attached to neck tape that was permanently worn whilst in hostile waters. With precious little clothing on, on reaching a freezing cold upper deck: all seemed to be normal. Traveling at the lowest speed for dropping depth charges, the ship had dropped a full pattern of ten charges, six of them being rolled over the stern. 2350hrs would have been the normal time crew members would have shaken their ‘relief’s’: that wasn’t necessary. An unwanted diversion, the last for the trip.

Merchant vessels and most of their escorts parted company, with merchant ships proceeding to British ports with much reduced escort. The bulk of the naval contingent proceeded to Scapa Flow arriving in early October..

A few days to rest up before the next task, carrying out harbour routine as described earlier. Some Volage crew members took the opportunity to spend the day at Kirkwall the islands capital. With cobbled stone streets and quaint little shops on a bleak and a ‘scotch misty’ day, it wasn’t a sailors usual ‘run ashore’. Looking back, was it an opportunity missed, albeit so briefly, to be involved in a culture considerably different from what our lives had been? Just one day at a very young age: perhaps not.

A not so typical operation:

Mid October , the Captain and a couple of his officers proceeded in his gig across Gutta Sound the destroyer anchorage in Scapa Flow, to a Senior Officers briefing. With their return ‘buzzes’ (rumours) were rife around the ship as to what our next operation would be. Officers stewards always a good source; or perhaps a signalman.

Late afternoon, the same routine for every time the ship leaves harbour commences, the broadcast over the Tannoy system: “Special sea dutymen close up. Close all X and Y doors. The ship is to assume category state one for sea”. In other words, those upper deck seamen required to make the ship ready for sea, securing lifeboats, bringing the anchor cable inboard etc., all report to their stations then advise the bridge that all is ready. All watertight doors and hatches to be closed and in most cases, four heavy dog clips set to secure each opening. From then on, open only for the purpose of passing through.

The duty H/F D/F operator, possibly me, would already have opened up watch on the D/F receiver on a designated U-boat frequency . There, until the ship returned to harbour, the duty operator would listen in to the German broadcast station sending messages to U-boats and log all messages. As these messages would obviously be in the German Naval Enigma code (four letter groups) from DAN it would be little different from listening to our own broadcasts (four figure code) from Whitehall. The difference in the case of the German broadcast would be that U-boats on sighting a vessel would immediately transmit a message to its base on the broadcast frequency, a message that could be identified as coming from a U-boat. DAN would repeat the message back at the next opportunity and give it a serial number.

The Main W/T Office is manned at all times at sea or in harbour. With staff divided into three ‘watches‘ at sea: one watch on duty and two off. On proceeding to sea, additional lines of communications would be opened. One would be ‘Distress Wave’ on 500k/cs. HMS Volage being flotilla ‘Half Leader’ would have its unique responsibilities, so other lines would be opened. The most important line would be the W/T broadcast from Whitehall where messages in morse code were continuously received. Every message would commence with the identification GBXZ followed by a number and its priority. There will probably be many a surviving ear still ringing from those 4 letters.

The rumbling of the anchor cable would tell that the buoy to which the ship was attached, had been slipped. The vibrations of the screws turning: the engine room staff were closed up and the ship under way.

In a darkening overcast, with a strong wind blowing, freezing rain squalls now and then, six ‘V’ class destroyers in line ahead, followed by six of the ‘W’ class, would pass through the defence boom nets that blocked off the entrance to the harbour, into a strengthening wind and rising seas. For all those open to the elements: not the most pleasant of experiences but Duffel coats, oilskins and thick woolen underwear and gloves helped to keep most of it out..

The destroyers are escort for the aircraft carrier Formidable and a couple of cruisers. A very small fleet when compared with the usual fleet which included a battleship and a number of carriers, that sails as distant cover(200 miles away) from a convoy on its way to Russia. Thus this smaller fleet , once out in the open sea takes up cruising positions with a line of destroyers in the van (ahead) usually referred to, in nautical parlance, as the A to K line. Volage was out on the port wing of the A to K line. The heading is north at an economical cruising speed of 17 knots.

Soon it’s dusk, and test “Action Stations” is ‘piped’ with all hands going to their designated station for action. A procedure carried out at dawn and dusk each day should the crew not already be in such a state of readiness. Dusk ‘Action Stations’ do not last long, mainly all personnel reporting that they are at their action stations. Tea for those off watch is partaken, and on destroyers the duty ‘cooks’ will clear away the utensils used and after dark take the ‘gash’ bucket and dispose of all the day‘s refuse. Off duty crew members settle down for the evening.

About this time, the ‘officer of the watch’ does his ‘rounds’ of the ship, making sure all is shipshape, no one is missing and that everyone is in the correct ‘dress of the day’. For lower deck ratings this means the usual daytime dress less the blue collar with its white stripes. All is well. The ’middle’ watchmen (midnight to 0400) most probably had turned in, in their hammocks.

“Out lights. Pipe down” would be piped 2200. Although, at sea in heavy weather the lights would be out well before the deadline. A faint blue ‘police’ light would be left glowing. Hammocks would swing to and fro in unison as the ship rolled but with the sea in its stormy state, the crashing down into troughs and then rising upon to the next swell, the momentum felt in the hammocks would be of the body feeling heavy as the ship lifted, to feel weightless as it dropped into the next trough. The hammock strings (known as nettles) creaking in protest under the strain. But it was so nice to be in one’s hammock after the lurching unsteady tiring hours in an upright position.

10 minutes to midnight, those going on watch would be awakened to go through those water-tight doors and hatches, to go on watch for the next four hours. It’s a little ghostly going along the passages with only a dim blue light, humming of engines and the ping ping ping ………of the tannoy sounding out the ASDIC transmitter constantly searching for the elusive U-boat. At 0350 the watch changing exercise is repeated.

A routine day followed. The fleet is now north of the Faeroe Islands and still heading north, still in stormy weather. The days are shortening and the other ships have disappeared in the gloom by 1600. The occasional message is received by flashing lamp. Such messages are kept to a minimum: we are in U-boat hunting grounds and there is a convoy in the area. Nothing but sea clutter and rain squalls are evident on the radar screens. The D/F operators have monitored a couple of U-boats sending ‘sighting reports’ message but they are distant and not in the direction of the convoy we are covering, so ignored. The W/T office has received many coded messages, from Whitehall, some are administrative, there would be known U-boat dispositions..

Another short autumn day passes. Then, during the ‘last dog’ watch a signaling lamp from the Senior Officer of the fleet is seen flashing. The signalman writes down a message which is in code. Unexplainably the message is indecipherable. Something was missed at the briefing back in Scapa Flow!!. Formidable and the rest of the fleet, make a 90 deg turn. Volage continued on its original course. Gale force winds and enormous seas are still running.

After a very short space of time, the radar plot reports: “echo bearing Green 90”. Echo was about the size of a U-boat conning tower. The echo disappeared into the sea clutter on the radar’s each time it went down into the trough of a wave. The night is dark and stormy. The ship slowed down to just a few knots which brought most of the crew, not on watch, to the upper deck to find out the cause.

A signalman with a 20inch signalling lamp, being used as a searchlight, directed it onto an object a few hundred yards off the starboard beam. As seen through the binoculars on the bridge, it appeared to be a small boat with men waving from its stern,

Volage slowly manoeuvred until it was alongside. Then as the gunwhale of the small vessel rose on a wave until it was level with the upper deck, the Bos‘n , a very powerful man, grasped a man from the boat and pulled him inboard. One by one they were brought on board until all men from the stricken vessel was safely onboard Volage. The crippled vessel was then left to drift away.

All four of those rescued were taken straight to the sick bay. A story that came out of the sick bay was that those men saved were two Norwegian, one Frenchman and one Belgium. There were originally seven men that had escaped from Norway weeks earlier but before having gone far they were sighted by a German patrolling aircraft who flew down at them firing its machine guns killing two and wounding another and damaging the fuel line.

The two men that had died were put overboard. The injured man died after some days and he too was put overboard. They were in sight of the Shetland Islands when their fuel ran out. Left to the mercy of the elements they drifted north. Day after day went by, food ran out and being subjected to the violent weather the fleet was also enduring, had given up all hope of survival.

After picking up the castaways, Volage rejoined the fleet. Only speculation could offer an explanation that resulted in so doing but communications obviously played a part. The off duty crew returned to the mess decks, wet and cold in many instances. At least it had been an unusual break in the routine. The fleet proceeded to carry out its objectives

After the carrier’s aircraft attacked radar stations and shore establishments, rumour had it that smoke was seen to be coming from the Tirpitz’s funnel and the fleet not being able to tangle with a battleship, prudently departed the area in some haste.

Volage’s communications staff were well pleased with the situation. After two and half weeks, the communication’s mess deck was dank and less than a pleasant place to be. The mess being two decks down from the upper deck, round about sea level when it was calm. The secured hatches ensured that little fresh air reached the mess deck. Riveted plates that made up the ship’s side would allow some seepage in especially violent seas. Water always seemed to make its way through closed air vents that came down from the upper deck resulting in the mess deck being continually wet to varying degree.. The puncalouvres shaft that came through each mess decks produced some airflow that left much to be desired when the main armament was fired as this action caused the smell of burnt cordite to permeate through the system and had a smell akin to sewerage outlet. Wet clothing, from those whose task required them being on the upper deck, the signalmen as an example, took ages to dry out and added to the discomfort, as well as the perpetual cigarette smoke, as most members on the mess were smokers. The odd thing was, that it was all accepted as normal - well I suppose.

The final act was for the captain and his chosen officers to attend a debriefing and probably a please explain to the communications breakdown. The remainder of the crew went about its harbour routine with drying out and cleaning ship at the head of the priority list.

A number of unbelievable coincidences had ensured the rescue of the motor boat‘s occupants. The ship’s crew was kept clear of the survivors who were taken off at Scapa Flow with only a few persons seeing their departure. Where did they go? To be interrogated I suppose, but the story doesn’t really end.

Another operation of attacks on shipping off the Norwegian coast, with aircraft carrying out minelaying operations. Fleet operations were basically the same as before but with Volage and other destroyers on the return voyage calling in at the Faero Islands for refueling. Whilst at the fuelling wharf, a number of children surveyed the ship with one young boy showing some displeasure at our presence called out: “My sister likes Germans”. A laugh from crewmembers on deck was all it achieved. Then it was back into Scapa Flow another operation completed. After passing through the boom nets, the sea settled down but there was a strongish wind blowing but as usual, a seaman was put on the buoy to which Volage was attached while in the sound. On the first approach, the ship hit the buoy knocking the seaman into the freezing cold water. The second approach was a repetition of the first. The seaman totally unhappy with the events let it be known to all by his language aimed at the bridge. Volage went to anchor until the conditions improved

It’s dark in Scapa. The signal goes out that a midget submarine might be inside the harbour. Destroyers are sent in search. Volage is in dry dock due to an incident when it damaged a couple of stern plates. Repairs have been completed but it is decided to remain in the dock until morning. No midget sub has been located after a thorough search and the searchers returned to anchor. HMS Wizard has been one of the searchers and has its depth charge crew standing by as the ship returns to its anchorage. Tragically, the order to drop anchor the order was also received by the depth charge crew with the result that the anchor and depth charges were dropped at the same time with catastrophic results to the stern of the Wizard. From memory eight crewmembers were killed with the after section uninhabitable. Volage was hurriedly moved from the dock at first light and Wizard that had been kept afloat by tugs, moved in.

Volage exercising with HMS Howe in refueling at sea, erred slightly too close to the battleship and was sucked in to its side. The damage was minimal to Volage but an escape hatch to a messdeck was damaged and necessarily welded shut. The Captain, Commander Durlacher was nick named ‘Crash’ by the crew.

One of the last operations of the year saw a fleet off the Norwegian coast again for air attacks on targets in Bodo/Sandnessjoen, Lodingen and Kristiansund North areas. This was a particularly interesting one for me as I was directed to monitor a given frequency and was soon receiving messages in abbreviated German from the usual callsigns that could be ships or shore establishments.

There were numbers that corresponded with the likely number of aircraft in waves from the carriers, followed by locations. Soon afterwards similar messages were received from reporting points using different callsigns. Then from a third and fourth locations. A short while later the signals were being received and could be discerned as the aircraft traveling in the opposite direction. Much of the morning watch was spent thus reading morse code at a speed as fast as the German operators could send. A story unraveled, however, my logbook was collected up at the end of the forenoon never to be sighted by me again.

With December, Volage was directed towards Rosyth anchoring in the Firth of the Fourth, there with instructions that no crew member could go on leave until all of the asbestos had been removed from the bulkheads. An asbestos lagging that had been attached to bulkheads around the ship in preparation for the cold waters on the way to Russia. As well as the removal of the asbestos the ship had to be de-ammunitioned. So, while groups of men were loading asbestos into barges other groups were carrying ammunition to other barges.

It was my lot to be on the first watch for leave so the following day after getting ration cards and railway warrant and leave pass, I boarded the train that took me over the Firth of the forth bridge and south. A phenomenon experienced by most servicemen: “When are you going back” With rationing and blackouts, little in the way of entertainment in a small, largely evacuated town and just about all of my contemporaries away, it was another world and one did miss one’s shipmates. The leave was over, a couple of train changes and its back in Edinburgh and Volage the scene of much activity alongside in Leith..

Christmas 1944 is spent in Leith. A couple of trips up to Edinburgh. Some kind person arranges a party for sailors away from their families. I am advised to prepare for a move to HMS Collingwood to learn Japanese morse code and communication system. Early January I bid a sad farewell to all my shipmates aboard a ship that I have become much endeared, leaving my comfort zone.

* * * * *

Volage joined the East Indies Fleet. My Japanese morse course was a story in itself because I had spent three weeks of a four week course when my services were required on another destroyer desperate for a Tel(S). So without completing my course, I soon found myself on a brand new ship doing its sea trials, special gunnery trials using Mosquito aircraft as targets!! (and FH4 calibration) before heading for the Pacific.

Here I am a world away from the frozen world of northern Russia. Much had changed, for one I had had to learn to type using a telegraphic typewriter in order to receive the high speed morse code as transmitted by the Americans. I was however, in the same world as Volage and it was later in Ceylon that I learned from an eye witness of Volage’s exploits as it operated out of Trincomalee.

I learned that on operation in Stewart Sound in the Adaman Islands, it had been fired on by shore batteries and that three men had died with several wounded. Also of attacks on Japanese shipping. The ship’s history is well known to me up until its being broken up but it is not my story.

In retirement

With HMS Volage in my background, my story takes a twist. With the ‘Cold War’ losing its intensity, the Russian government made medals available to all those that had aided the then Soviet Union in its struggle against Nazism in the “Great Patriotic War”. The medal being recognized by the British Medals and Honours Division who also permitted the wearing of this medal on ceremonial occasions.

Here in Australia, there were several hundred ex Royal Navy members who formed an association that became known as the “Arctic Convoy Veterans Association of Australia” Of which I had the honour to serve as their National Co-ordinator for many years. Sadly our numbers have been considerably depleted over recent times. Those remaining are in their mid eighties to mid nineties most showing the ravages of the years “They shall not grow old as we who are left grow old”. Below is a picture of me after attending a school celebration of Australia’s ANZAC Day.

To the people of Pocklington, may I send my best wishes and thank you for having given me the opportunity to write a little of life aboard the ship you so patriotically adopted back in the days of deprivation and danger that we all shared.

Motif used by Arctic Convoy Veterans Australia

Arthur W. Carter

R.I.P.

(2/6/27 - 25/1/2019)

8/6/2019: From an email from his only grandson Wayne McGarrity, I learned that Arthur Carter passed away in the Prince Charles Hospital Brisbane, Qld., Australia on the 25th January 2019. Arthur was the last surviving member of the Arctic Convoy veterans association of Australia. Arthurs ashes were spread with those of other convoy veterans. The ashes of these veterans are scattered at the mouth of the Caboolture River. Deception Bay Qld Australia. They are in a position to safely oversee the passage of vessels passing the river mouth. There is also a monument in Deception Bay in memory of the 2,773 men that lost their lives serving in the Arctic Convoys.

This research is being sponsored by Hull Maritime.

|